Drop Boxes Tell Tale of US Democracy in 2020

“If things could talk, then I’m sure you’d hear a lot of things to make you cry, my dear. Ain’t you glad, glad that things don’t talk.” – Ry Cooder

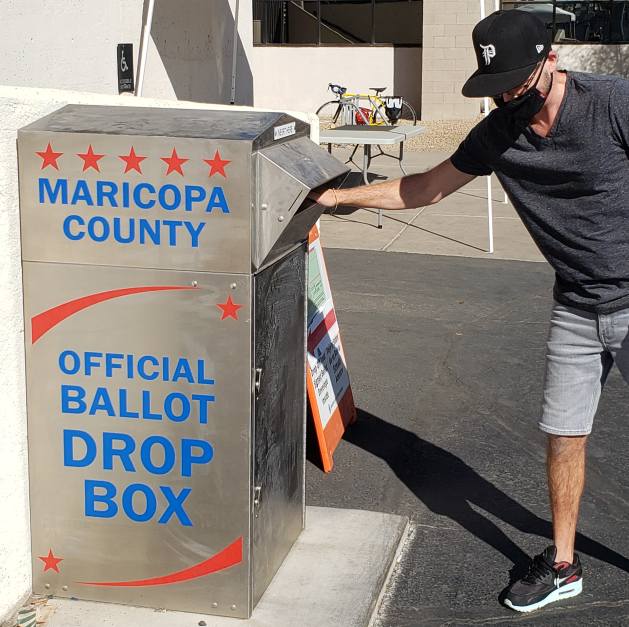

Drop box outside the Maricopa County Recorder’s office in Phoenix, Arizona. Credit: Peter Costantini.

PHOENIX, ARIZONA, US, Nov 2 2020 (IPS) - It sits stolidly, bolted onto a concrete base outside the Maricopa County Recorder’s office in Phoenix, Arizona. Weighing in at around 600 pounds, it sports “anti-tampering features” and “heavy-duty, all-weather construction”. Security agents check it periodically and it appears to be watched by a camera. As I scrutinize it, a man in an SUV pulls up and deposits a ballot in its slot. He tells me he votes this way every election, then drives off.

Despite its impassive demeanor, this drop box and its fellows have flirted with media celebrity. If they could talk about how they came to be deployed – or not – this year, they could tell a tabloid-ready tale teeming with lurid details about the sad state of democracy in these United States of America.

But this one didn’t even offer a “no comment”, so let’s tease out its story from other sources.

Voting procedures in the U.S. vary widely from state to state, in a matrix of Byzantine complexity. Several states conduct elections nearly completely by mail, and most others offer mail-in ballots as a routine option. A few, however, allow absentee ballots only on request and for restricted reasons.

Most states permit bypassing the U.S. Postal Service by dropping mail-in ballots off at a drop box or a polling place, while only four states ban drop boxes. Many states also allow early voting in-person for days or weeks before the election as a way to forestall crowds on Election Day. In several other states, though, permitted voting methods are unclear or pending litigation.

Voting procedures in the U.S. vary widely from state to state, in a matrix of Byzantine complexity. Several states conduct elections nearly completely by mail, and most others offer mail-in ballots as a routine option. A few, however, allow absentee ballots only on request and for restricted reasons. Most states permit bypassing the U.S. Postal Service by dropping mail-in ballots off at a drop box or a polling place

This year, the COVID-19 pandemic left many voters loathe to enter a polling place to vote out of fear of exposing themselves to the virus. Numerous volunteer poll workers, who are often elderly, also decided to sit this election out. In response, many states decided that numbers of polling places would have to be reduced.

Given the unusually high expected turnout, though, this would likely mean long lines of voters. Most states had long allowed “absentee ballots” to be mailed in by those away from home or with physical limitations. So this year, in many places, mail-in voting was expanded, often by sending a request form for a mail-in ballot to every registered voter.

States with all-mail voting (including my home state of Washington) have made voting more accessible to all voters for many years with hardly a whisper of misconduct or controversy. President Donald Trump himself has voted by absentee ballot.

But as the phenomenon gained momentum, he and a chorus of Republican politicians began to raise a hue and cry against mail-in voting, accusing it of fostering massive fraud, in the face of overwhelming evidence to the contrary.

Throughout most of the country a pattern emerged: Democrats were tending to vote in advance by mail or drop box, while Republicans, perhaps heeding presidential warnings, were more likely to plan to vote in person on Election Day.

Then in June, Louis DeJoy, a major Trump and Republican donor, took over as Postmaster. Without missing a beat, he began to dismember the United States Postal Service – a long-term goal of the Republican Party, which has sought to privatize it and break its labor unions. DeJoy reportedly has significant financial interests in firms that compete or do business with the USPS.

The new Postmaster removed essential equipment, fired experienced management, and eliminated employee overtime, resulting in substantially slower mail delivery in some areas. All this obstruction came at the beginning of an electoral season when a major surge of voters, particularly Democratic ones, were counting on reliable, speedy delivery of ballot requests and ballots.

With predictable chutzpah, Republicans in several states have sued to require that mail-in ballots be counted only if they are received by Election Day, rather than if they are postmarked by that day, which is the norm. This would put mailed votes at the mercy of politically motivated postal slowdowns.

I couldn’t find one of the junked mail-sorting machines that was willing to go on record.

Credit: Peter Costantini.

Public outcry and Congressional hearings made DeJoy back off on some off his restrictions, but the capacity of the post office to handle high volumes of ballots remained in question. Many voters who had received mail-in ballots became concerned that, if returned by mail, they might still face delays.

Yet entering polling places to drop them off added some risk of exposure. One good solution was to deposit the ballots into the secure drop boxes that roughly two-thirds of the states and many localities already provided outside polling places and in other locations.

Last June, the Trump campaign had sued the State of Pennsylvania for adding ballot drop boxes around Philadelphia, the state’s biggest city, with a combined Black and Hispanic population of 58 percent. Both of these groups vote heavily Democratic.

A Federal judge appointed by Trump found that the campaign “failed to produce any evidence of vote-by-mail fraud in Pennsylvania,” including fraud related to drop boxes. A research project by the Brennan Center for Justice calls voter fraud “a myth” and explains: “Extensive research reveals that fraud is very rare. Yet repeated, false allegations of fraud can make it harder for millions of eligible Americans to participate in elections.”

Nevertheless, Trump later tweeted that ballot drop boxes are a “big fraud” and “make it possible for a person to vote multiple times”. Twitter reportedly put a notice on the tweet saying that it violated its “civic integrity policy.”

The response of some other Republican officials has been – you’ve probably guessed by now – to severely restrict the number of drop boxes. In Texas, Republican Governor Greg Abbott imposed a limit of one drop box per county.

The populations of Texas’ 254 counties, however, vary from under one hundred to several million. Democrats fought this restriction in court, but lost. Now Harris County, where Houston is located, has one drop box for nearly 4.8 million residents. Not coincidentally, the county’s population is around 60 percent Black and Hispanic.

Similar limitations on drop boxes have been imposed by the Republican Secretary of State of Ohio, also provoking a legal rumble. My Phoenix drop box, though, seems to have job security. Arizona’s Democratic Secretary of State has rolled out a well-distributed network of its siblings, some of them in drive-through locations. This year, over 80 percent of Arizona voters will send in an absentee ballot, either through the mail or via drop boxes, without perceptible controversy.

Still, the malevolent hybrid of Machiavellian yet transparent voter suppression, bred by the coordinated attacks on mail-in voting and drop boxes, is a lowlight in a campaign full of Republican assaults on democracy. Enumerating them all is a job for historians – and civil-rights attorneys. But another one stands out for sheer vindictiveness.

In most states, prisoners are not allowed to vote, but ex-felons who have done their time and finished probation have their civil rights, including voting, restored. In Florida and a few other states, however, released ex-felons were not allowed to vote again except by special dispensation.

In 2018, Florida voters approved, by a two-to-one margin, a constitutional amendment that restored voting rights to ex-felons. But not long after, the state’s Republican legislature intervened and added a provision that to have their rights restored, ex-felons had to pay all prison fines, fees and restitution charged against them during their incarceration.

Most people emerge from jail with little or no cash on hand, so this amounted to revoking their newly reinstated suffrage. A legal challenge initially struck down the legislature’s changes, but a federal appeals court reversed the lower court and upheld the pecuniary provisions, although confusion persists on how they should be carried out. Out of the 1.4 million ex-felons who initially had their rights restored, a disproportionate number of them people of color, it appears that fewer than one-quarter of them will be able to vote in this year’s elections.

If this sounds like something right out of Jim Crow, it’s not far off. Among the many ways that Black voters were disenfranchised after the end of Reconstruction was imposition of a poll tax, which had to be paid in order to vote.

Few African Americans could afford the cost, and those that could were often denied their rights by other chicanery or violence. The first judge’s ruling against the legislature said the financial requirements amounted to an unconstitutional poll tax.

This chaotic landscape of multi-faceted voter suppression has grown worse this year, but it has roots at least a century and a half old. Just a bit more than a decade after the Civil War, repressive measures like the poll tax combined with outright terrorism – lynching, arson and mass murder – to snatch away the rights and economic advances Black people had won since the end of slavery.

This continued up until the civil rights movement of the 1950s and 60s, with the Democratic Party playing the dominant role in denying democracy across the South. With the social changes spearheaded by the movement, and the passage of the Voting Rights Act in 1965 under Democratic President Lyndon Johnson, the center of gravity of Southern racism moved into the Republican Party, which embraced it tightly with President Richard Nixon’s “Southern strategy”.

A political rallying point of the segregationists was the concept of “states’ rights”, the idea that they could defend Jim Crow against Federal efforts to desegregate by invoking the primacy of each state to determine its own laws. Federal enforcement helped Black and liberal movements and politicians roll back some of the worst abuses.

Under the Voting Rights Act, most of the states of the South and a few others with a history of discrimination were forbidden to make changes in their electoral laws without Federal approval. But then in 2013, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in Shelby County v. Holder that the patterns of discrimination the Act guarded against were no longer occurring, and removed the requirement for federal supervision of voting laws.

Very quickly, many of those states re-enacted restrictions on voting, some more subtle than before, but aiming towards the same old goal: making it harder for people of color people to vote.

Ironically, along with the reactionary effects on voting rights in conservative-run states, the resurgence of states’ rights and loosening of federal control has provided more leeway for some blue states to enact liberal and progressive reforms despite the Trump administration’s opposition.

All but one of the states that have chosen all mail-in voting are run by Democrats. States and cities have enacted sanctuary and immigrant-justice laws in defiance of regressive federal immigration regulations and enforcement.

Underlying all the political and legal hurly-burly, three structural elements deeply entrenched in the U.S. Constitution and statutes help ensure that fundamental democratic principles such as neutral, fair electoral administration and “one person, one vote” remain problematic.

Unlike many other countries, the United States does not have a fourth, electoral branch of government, independent of the executive, legislative and judicial, that could standardize electoral law and practices nationally.

Some jurisdictions have independent, non-partisan electoral commissions, but they are often appointed by a partisan executive. Many electoral authority posts, though, are partisan, and as the 2000 Florida fiasco and Bush v. Gore made indelibly obvious, political pressure and voter exclusion in high-stakes contests can bulldoze even-handed election administration.

The U.S. has a bicameral legislature with a Senate comprising two senators from every state, large or small. This is perhaps the most blatant Constitutional violation of “one person, one vote”: a citizen of the most populous state, California, with a nearly 40 million residents, has only a tiny fraction of the representation of a citizen of the least populous one, Wyoming, with under 600 thousand. Both states have two senators.

The old justification that the collegial deliberations of the Senate would restrain the tendencies toward mob rule in the House of Representatives has been rendered ridiculous by the Republican Senate leadership’s comportment over recent years, but it always reeked of elitism. Senators from smaller states have often been excessively beholden to the biggest local industries: Henry “Scoop” Jackson of Washington state, for example, was known as “the Senator from Boeing” for his fealty to the dominant aircraft manufacturer.

In the United Kingdom, by contrast, the House of Lords, the U.S. Senate’s counterpart, has been reduced to a mainly advisor body with little political power. Democrats have long contemplated trying to bring in the District of Columbia, and possibly Puerto Rico, as new states with two senators each, but this would be a heavy lift politically. It’s hard to see a feasible reform short of major changes in the Constitution.

The Electoral College is another negation of “one person, one vote”. Although numbers of electoral votes are very roughly proportional to state populations, they still give considerably more representation to smaller, more rural, whiter states. The winner-take-all nature of the electoral vote, with the exception of two states, means that it frequently does not reflect the popular vote.

The Electoral College is an 18th Century institution that gives far too much leeway to the whims of appointed electors, and can be too easily overridden by state legislatures. It has become enough of an embarrassment that some reforms are attracting public attention. The best known is the National Popular Vote Interstate Compact. Under it, states pledge to give all their electoral votes to the candidate winning the national popular vote, but this goes into effect only after states representing 270 electoral votes, the majority needed to elect a president, have signed onto the agreement.

Elections in 2016 and 2000, in which the winner of the Electoral College lost the popular vote, have inflamed bitter national divisions and installed governments that led the country into ongoing catastrophes. A previous contested election, in 1876, was resolved by both parties agreeing to end Reconstruction, snatching away the barely restored civil and human rights of Black people for most of the next hundred years.

The country’s rickety electoral infrastructure might not be able to weather another such blow.

For one more electoral cycle, at least, the salvation of democracy here may lie in the same decentralization that has caused such frustration. Beneath the brazen attempts to disfigure democracy, there remains a strong, grassroots culture of fairness.

There are millions of voters willing to stand in long lines, even if they’re caused by political manipulation, and puzzle out confusing regulations in order to cast their votes. And there are thousands of local officials and volunteers of all political persuasions who are willing to work long hours and brave stifling bureaucracy to make sure that all votes are counted.

I returned to check on the original drop box. It was clearly the strong, silent type: no complaints, no publicity seeking, it just did its job. I took a few more pictures. A security guard shook his head and told me that he had never seen a drop box attract the paparazzi like this one.

- ADVERTISEMENTADVERTISEMENT

IPS Daily Report