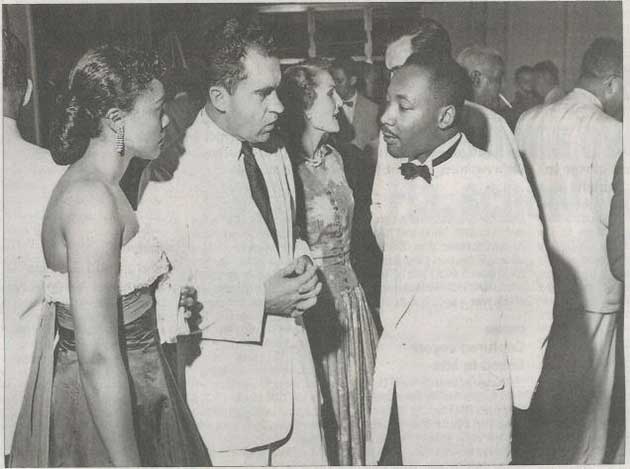

How My Dad Captured This Famous Photo of Martin Luther King Jr.

In commemoration of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.’s birthday this iconic photograph of the first meeting of King and Richard Nixon will be displayed at the Florida Museum of Photographic Arts, 400 N. Ashley Dr., Tampa, through April 19 as part of the inside exhibition, “Griff Davis- Langston Hughes, Letters and Photographs, 1947-1967: A Global Friendship. For more information about the exhibit and to learn more about Griff Davis via video, please go to www.fmopa.org.

TAMPA, Florida, Feb 8 2021 (IPS) - My dad, Griff Davis, was a boyhood friend of Martin Luther King, Jr. They ran in the same crowd and, after graduating from Morehouse College, stayed in touch their whole lives. Dad, who was both an international photojournalist and U.S. Foreign Service officer, captured a famous photo of a rising “M.L.,” as they called him in Atlanta, and Vice President Richard Nixon meeting for the first time in newly independent Ghana in 1957. That photo couldn’t have been made in America at the time.

Dad was 24 when he graduated from Morehouse in 1947. After M.L. graduated a year later at 19, they both set out to make their lives, knowing that they had a right to dream and the tools to make those dreams come true. They only needed experience.

In 1947, Langston Hughes arrived at Atlanta University as the visiting professor for creative writing. Recognizing that Dad was the photographer for the campuses of the Atlanta University Center and the Atlanta Daily World, Hughes adopted him as his photographer in Atlanta.

Dad became the first roving editor of Ebony magazine at Hughes’ recommendation to its founder and publisher. He subsequently graduated in the Class of ‘49 from the Columbia University Graduate School of Journalism while renting a room in Hughes’ home. It turned into his home base while working as the only African-American international freelance photojournalist for Black Star, the first privately owned picture agency in the United States. His work appeared in Fortune, Ebony, Time, Modern Photography, Steelways and Der Spiegel.

During this time, he made three separate trips to Liberia, which with Ethiopia were the only independent black countries in Africa and among the charter members of the United Nations in 1945.

My parents returned to Liberia in late 1952 after Dad passed the foreign service exam, the beginning of his 35-year career. Unlike their white counterparts, African-American Foreign Service officers at the time were posted by the U.S. State Department only to Liberia or Haiti.

When Prime Minister Kwame Nkrumah led the Gold Coast to independence from Britain in 1957 to become the new nation of Ghana, our family was ending a four-year tour in Liberia. Back in the United States in 1955, Rosa Parks had been arrested after refusing to give up her bus seat, and King had come to national prominence as the leader of the Montgomery bus boycott.

Vice President Richard Nixon and Patricia Nixon led the official U.S. delegation to Ghana’s Independence Day ceremonies — Nixon’s first trip to Africa. King and Mrs. Coretta Scott King had been invited by Ghana’s prime minister himself on the heels of the end of the Montgomery bus boycott. It was also the Kings’ first trip to Africa.

Having attended Lincoln University, Kwame Nkrumah was very aware of the racial dynamics in the United States and had been following the American civil rights movement. He could equate it to the colonialism in his own country. Recognizing the common fight for freedom between the two movements, he used the Independence Day celebrations of Ghana as a global platform to bring key people together. This included Ralph Bunche, the first person of color to have won the Nobel Peace Prize, in his new capacity as undersecretary of the United Nations.

The U.S. Information Service (USIS) assigned my Dad to cover Nixon’s visit to Liberia and Ghana, one of only 20 official photographers to cover Ghana’s independence celebrations. It was the first African country to become decolonized.

The Kings arrived in Accra, the capital, on March 4, 1957 and attended a reception at Legon University. That’s where he met Nixon. As the official photographer for the Nixon delegation and former photojournalist, my father took the picture of their first meeting.

Dad said, “When they met, Nixon invited M.L. to come by his office the next time he travelled to Washington. … It was ironic to me that Montgomery, Ala., and Washington, D.C., had to meet at Accra, outside the United States. However, it was only a short time later that M.L. and his nonviolent movement entered upon the national scene in America.”

The next time my father saw M.L. and Coretta Scott King was back in the U.S. at my Dad’s 10th year class reunion at Morehouse in June 1957. They were building the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC). In 1963, my father attended the March on Washington in Washington, DC and heard M.L. give his “I Have A Dream” speech. It reminded him of their teachings at Morehouse. He last saw M.L. at the Capitol in Montgomery at the conclusion of the March from Selma in 1965. In 1966, our family was posted to Nigeria. M.L. was scheduled to visit Nigeria the week after he was assassinated.

All through the years since their college days, M.L. and Dad exchanged greeting cards at Christmas. This is the message in the last Christmas card:

“We who know we are brothers,” M.L. said, “have a duty to bring others back into the broken family of man, into our world house. In the context of the modern world, we must live together as brothers or we shall perish divided as fools.”

This story was first published by Tampa Bay Times

Dorothy Davis, president of Dorothy M. Davis Consulting and Griffith J. Davis Photographs and Archives, is a member of the board of directors of the Tampa Bay Businesses for Culture and the Arts and United Nations Association-USA Chapter Tampa Bay Chapter. She serves on the Board of Directors and program committee of the St. Petersburg Conference on World Affairs.

- ADVERTISEMENTADVERTISEMENT

IPS Daily Report